|

|

本帖最后由 太白侠 于 2017-9-6 19:40 编辑

西方也有“针灸”和“医卦同源”——谈谈中西传统医学,占星术和针灸史(2011-07-09 11:27:45)[url=] 转载▼[/url] 转载▼[/url]

(Ben Kavoussi MS, MSOM, LAc 原作 邓旭峰译)

译者按:

记得在大学上国际政治战略时,就和教授聊到传统文化问题.教授不客气的说:"每个国家都有一群人说他们的文化是多么的独特,这证明了一堆人对世界思想史的认知是零.我们这些真正研究历史的人都知道这世界上根本就没什么稀奇的思想,都是那几种观点在世界各地跑来跑去,然后用当地习俗和语言包装一下然后就变成了"独特文化"粉墨登场.

前阵子读到了方舟子老师的佳作"西方也有阴阳五行",正好又在scinecebasemedicine.org 上读到了一篇最新的论文比较中国的四时节气,经络之类的理论和"西方"世界(实际上在不少欧洲人的心目中阿拉伯世界是"东方")的宇宙观和星象医学的相似处,当然同时也把针灸再度批判了一顿,我就决定把这篇文章翻译出来以飨读者,题名为"西方也有'针灸'和'医卦同源'"--就算是跟进方老师吧,嘿嘿嘿.

中医的许多理论,在古欧洲和阿拉伯都能找到相似之处,所以中医不可能被世界接受的原因很简单--虽然中医骗子们成功的捏造历史并也的确在一时骗了不少人,包括一些知名学者,但实际上中医理论不过是古代世界共有的星象学及自然哲学的死灰复燃.当然中医理论不可能和传统西医一模一样,不过却是大同小异,科学有本事打倒传统西医,就也有本事打倒传统中医.没有任何理由认为中医能够逃过灭亡的命运,这只是时间长短问题而已.国家的中医保护政策和最近在欧美民间出现的反启蒙,反科学的运动结合是有可能把中医的气数延长数十年甚至百年,但最终结局基本上已经注定:历史的大方向是朝唯物,启蒙迈进的,历史上的反理性反科学思潮一向都是无疾而终.保护中医的任何行动不过是把大把大把的钱和时间投资在一座迟早要陷落的孤城里,孤城苦撑越久,消耗的人力物力,造成的灾难,就会越多.

论文里附有二张插图,想参考图片或者中英文对照的读者可进入http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/?p=583里查看原文.若翻译的不好请多包涵.若有任何指教或建议欢迎来信至killhealerfirst@yahoo.com交流切磋.

<标题:用针的星象学>

<作者按:以下文章节录于专题"不为人知的针灸故事".这份专题定于在二零零九年十二月在FACT期刊上刊出. FACT是一份中立的审核性杂志介绍并分析关于各种另类及补充疗法的证据.这篇论文认为假使真针灸和假针灸的效果在严谨控制下的实验是一样的,其原因是因为传统的取穴理论并不是基于实践,而是基于古代的宇宙观,星相学和神话.传统中医理论和中世纪欧洲与阿拉伯的星象医疗,放血疗法的基本理论极为相似.除此之外,许多人断言的针灸在中国学术医药传统上的主导地位并不被任何证据支持,因为在中国历史上的绝大部分时间,针刺,放血和烙印术是给民间不识字的江湖郎中用的.真正学过医术的中医师讨厌针灸并喜欢开中药方.>

"故天有宿度,地有经水,人有经脉"--黄帝内经(1)离合真邪论第二十七

针灸被认为起源于新石器时代(2,3)用作于治疗用途的的献血仪式,魔法刺青和穿体洞.新石器时代起源的假说有特伦蒂诺--位于欧洲无人居住的奥茨阿尔卑斯山的冰人身上的非装饰用刺青作为支持证据.这具被自然保存了五千二百年的的尸体上有一群像小十字架般的刺青,刺青的位置和传统针灸穴位非常接近.医疗照片显示这位中年男子患有膝关节炎,而刺青所在的位置正是传统上被认为与膝关节炎相关的点(4,5).相似的非装饰用途刺青在全世界各地世界里都被发掘到,包括美洲(6,7,8).医疗用的刺青仍然保存于现代的西藏,刺青落在特定的点上,染料里混合著药草.这些习俗主要是为了达成自然世界与灵性的平衡,同时也保护病人不受恶魔的恶念侵犯.看起来,这些新石器时代和铜器时代包含魔法与灵魂的传统在许多文化里演化成针刺和放血的系统,用来使人类健康与长寿.除此之外,为了治疗不洁的或过剩的血液,在许多文化里针刺也被认为可以影响一种精神力量的流动.这种力量在中国被叫做"气",在梵语里被称作prana,在希腊文里被称作pneuma,等等(9).这些观点都相似地混合了各种形而上及神秘的元素,让现代学者们难以把他们当作是分开的观念而去个别解释.

在中国,这种神秘的力量被认为是反应太阳在一年中由黄道运行过天体的轨迹并组成了一套叫作"经络"的网路,在英文中被唤作 Chinglo channels 或者是 channels, 或是 Meridians (法国大使 Soulié de Morant 在一九三九年使用这个单字描述经络).这些想像中的气路从头流到脚趾并连接了身体上大约三百六十个点(10).极有可能这些经络网路是一种循环系统的粗略模型--建立在一种认知上--一套有关于星象和太阳神话的信仰.这种认知也认为一个人的健康与命运决定于太阳,月亮,五行星的位置,彗星的出没和人的出生时间(11).在这种世界观里,人体每一部分被认为对应中国的星象学系统:十二地支中的一支,十二地支代表黄道上的十二段,每段长达二小时(三十度角).经络于是被命名根据他们阴与阳的程度--从太阳到厥阴,这些命名描述了他们与日月对应的位置(12).每条经络上有五个特别点,每个点有他们的特性--水,木,火,土和金.它们也代表了水星,木星,火星,土星和金星(13).这些点看起来反映了五个行星在他们对应地支里的运行位置.这些点也都有一个对应颜色,对应色来自于对应行星在晚上用肉眼观测到的颜色.金星是白色,木星是蓝绿色,土星是金黄色,火星是红色,而水星是"黑色"--因为在五个行星中水星最为黯淡.每个点也和一个方向,一段时间,一个季节,一组数字,一种味道,一个音符,一个内脏,一部分的身体,等等,这些观点存在于中国古代的"关联性宇宙观"(14)(按:天人合一,天人感应),和毕达哥拉斯和他学生的笔录所记载的神秘信仰里(15).在这神秘的世界观里,"气"的性质常被如类似以下的方法解释(16):

"中医理论的重要立论点是一种重要的生命力量"气",化育了宇宙中一切生命.气也可以被当作"气息"与空气,这种观点和印度的 Prana 相似,看不见,尝不到,闻不出,摸不著,但是气却弥漫著整个宇宙.气能够被传送或变质,消化作用把气从食物和水里取出并转送至身体里,呼吸作用摄取空气里的气并转化入肺,当这三种不同型态的气进入血液之后,它们转换成人体的气,在体内循环并构成生命的力量.气的质与平衡决定了人的健康和寿命. 其他文献提到气是"宇宙中普遍并赋予生命的灵力"(17)和"气生万物"(18).例如炼丹术士葛洪写到: "夫人在气中,气在人中,自天地至于万物,无不须气以生者也.善行气者,内以养身,外以却恶"(19,20).在"关联性宇宙观"的信仰里气的走向和地支的对应关系似乎是建立于地心说的宇宙观和与地心说相关的古巴比伦"天人相应"思想,认为天上的每一事物都对应到地上及人体.(按:As above, so below 出自于巴比伦文献,所以这里翻译成古巴比伦"天人相应")

"天人相应"的宇宙观或关联性宇宙观在古世界里极为普遍,从地中海东岸到北欧都有.最著名的证据是一个上面有神秘预言Corpus Hermetica的饰品.这些文字被认为是书写于一至三世纪的希腊化埃及并发展成希腊神学Hermes Trismegistus,相当于埃及的智慧之神Thoth.神学原文可能在四至六世纪时的系统性焚毁基督教文献时遗失或被销毁,但是其中的一部分--"绿宝石板",保存了下来并被回教徒翻译成阿拉伯文,再于一一四零年被John of Seville; 一二四三年被Philip of Tripoli翻译成拉丁文.在阿拉伯文版的绿宝石板里,博学家和炼金术师 Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān翻译道: "那天上的是从下方来的;那下方的是从天上来的;奇迹般的作为一个整体运行"(21).既然我们已经知道这种信仰在古世界里极为普遍,看起来为针灸基础理论铺路的自然哲学也是从这一套信仰里衍生出来.这套信仰在丝路上的国家如波斯,美索不达米亚,埃及,希腊极为普遍(按:中国也位于丝路上,理当不能例外)而且影响了在基督教统治之前地中海区有关于健康及安全的地区信仰并形成了东地中海神秘教(22)和灵知派基督教(23).这个假设被Gregor Reisch写的Margarita Philosophica(智慧的珍珠)里的一段所支持,这本书初版于一五零三年(24):

"异教徒们相信星座构成了伟大的宇宙体.这宇宙体,他们称作Macrocosm(大世界),被分割成十二部份,每一部分被位于代表的星座内的星星之力量控制.他们相信人体是整个宇宙的系统的模型,人体被称作Microcosm(小世界).他们发展出了我们现在(按:一五零三年)熟悉的"人体分割年历",把每一个星座放进人体重要的十二部份之一.

<图一>John de Foxton描述的中古欧洲的"黄道人"--Liber Cosmographiae,1408.

这张图指出星象对各区人体的作用.医生们用这张图来决定放血的吉时.图片由英国剑桥市The Master and Fellows of Trinity College提供.

在这个信仰前提之下,直到十七世纪之前欧洲医生行医用药的方式主要是根据星象计算,这种医术被称作Iatromathematics(医疗数学)(按:类似中国的术数),astrological medicine or astromedicine(星象医疗).他们然后整理了行星运行的表格并制作了星历表,又称阿方索星表.根据星座的联合,排序和与行星的角度来预测疾病是否能够成功被治疗--在他们放血,拔罐,烙印,手术或开药方之前(25).疾病的形成原因被认为是一种神秘的生命力pneuma流动受阻和四体液的不平衡--血,黄胆汁,黑胆汁和黏液,每一种体液也对应一种元素,一个行星,一种颜色等等根据欧洲版的"关联性宇宙观".治疗方式是在有利的星宫角度时扑灭过多的体液和其有害的压力.大部分的放血师会用"柳叶刀"把臂上,腿上或脖子上的静脉切开.他们会把止血带绑住一个地方,精巧的用中指和食指夹住柳叶刀后斜斜的或纵长的把静脉切开以避免大出血,然后用量碗来接血(26).在一开始的古典希腊放血法里,血从病源的附近被放出,但是后来的医生会在病灶的远出放比较少量的血.正确放血的程序不但要知道从哪里下刀,放多少血,而且要精通星历表

以便找到合适的放血时间.中世纪的医疗文献于是包含了星历表(volvelles)和被星座号志包围的人体图表--"黄道人"来表示特定星座对人体特定部分和器官(图一)和其对应放血点的位置(图二).

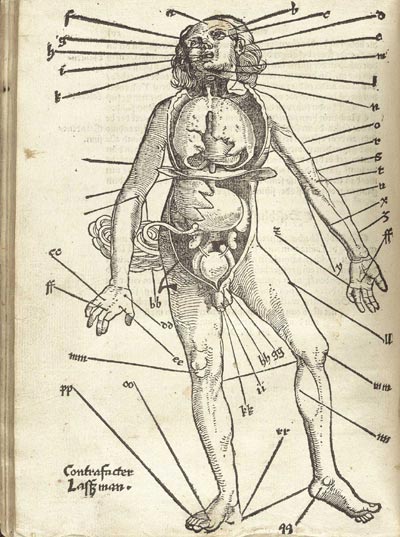

<图二>欧洲 Hans von Gersdorff 的"放血人", Feldtbüch der Wundartzney,一五二八年出版.

放血疗法可以用静脉切开或水蛭吸血达成,大部分的放血点都对应重要的(中国)针灸穴位,例如太冲穴,委中穴,后溪穴,合谷穴,曲池穴,中渚穴,尺泽穴,等等.图片由美国国家医药图书馆提供.

被星宫影响的重要身体部位是从头开始算起,属于山羊座一直到脚部,属于双鱼座.巨蟹座被认为是和肺病和眼疾有关,而天蝎座则影响阴部感染(27).根据假定的身体定点和器官的关系用刀刺,放血或是拔罐(阿拉伯文 Hijama)的方式去影响某个特定的器官或去减轻特定的疾病仍然在今日的回教世界极为普遍,而且连在Youtube上都有视频示范.同样的基础理论有可能也构成中国经络学说的起源(28),因为星象影响在人体上的分布和其对应的放血点,在中世纪伊斯兰和欧洲文献上的记载和经络学说里重要的,功能性的,关键的穴位极其相似(表一).一个我们要知道的重要事情是古代中国人知道有欧洲放血疗法的存在,而且一部分的阿维森纳的医书和其他阿拉伯和波斯文献也在元朝时被翻译成"回回药方"传入中国(29).中国针灸和放血疗法的关系更进一步的被(文法上的)事实证明:中国字"针"在认知上可以代表用粗糙的针穿刺,或是用任何锋利的物品做献祭,放血或小手术(30).除此以外,就如Paul Unschuld指出的,用不同的深浅程度(按:类似中国的针灸下针深度:天,人,地)作放血的使用时期早于中国人用针灸去调节气(31). 而且,在Linda Barnes的一本精彩著作里谈到了西方世界在中世纪晚期到十九世纪中期眼中的中国,中国人和中医,她提出了有说服力的论述认为有足够的中,(传统)西医之间的相似之处使我们可以做出假设,这两种医术"从同样的基础理论上成长"(32). <表一>中世纪伊斯兰,欧洲星象医疗和中国针灸理论的相似处(表后附例证解释)

西方星座--角度--区域/器官 ******VS****** 中国星座--时辰--经络/器官

山羊座--0~30--头部 *********************** 虎--寅时--手太阴肺经

金牛座--30~60--脖子,颈部 **************** 兔--卯时--手阳明大肠经

双子座--60~90--肺,手臂,肩膀 ************ 龙--辰时--足阳明胃经

巨蟹座--90~120--胸部,胃部 ************** 蛇--巳时--足太阴脾经

狮子座--120~150--心脏,上背 ************* 马--午时-- 手少阴心经

处女座--150~180--腹部,消化系统 ******** 羊--未时--手太阳小肠经

天秤座--180~210--肾脏,腰部 ************* 猴--申时--足太阳膀胱经

天蝎座--210~240--阴部 ******************* 鸡--酉时--足少阴肾经

射手座--240~270--臀部,大腿 ************* 狗--戌时--手厥阴心包经

摩羯座--270~300--膝部,骨头 ************* 猪--亥时--手少阳三焦经

水瓶座--300~330--小腿,脚踝 ************* 鼠--子时--足少阳胆经

双子座--330~360--双足 ******************* 牛--丑时--足厥阴肝经

例证:手太阴肺经上的列缺穴主控头部;合谷穴,手阳明大肠经的重要穴位,掌控脸部和喉咙;足太阴脾经上的公孙穴被用于治疗胸病及胃病;足少阴肾经掌控阴部;对应三焦的重要穴位委阳穴位于膝部;对应胆的丘墟穴位于脚踝;肝经上最重要的两个穴位,行间穴和太冲穴,位于脚部等等(33).注意星座每一个时辰移动三十度,每个小时五度.

令人费解的是,在中国漫长的医药史上有大部份的时间里,针刺和放血和中药的使用比起来是被认为一种民间大夫用的低俗疗法.正如历史学家Bridie Andrews Minehan 描述的:

"卑微的针灸师们要面对大量的小型手术.这两种技术:针灸和外科之间有许多重叠的部分.在帝制时代晚期,针灸使用手册里面图示的九种针里有手术用刀,烙铁,用作于放血的三角锥,也有我们现在所熟悉的针灸用针."

Andrews Minehan也提到了虽然在黄帝内经里常提到针,在中国历史上针刺术极少在其他书里被提及.根据记录,在纪元一千五百年左右穿刺和放血术几乎已被中国人全面放弃,最后中国和其他的东方国家终于采取行动要让针灸从东方世界上消失(34,35).在一八二二年,中国一道敕令禁止了针灸在太医院里的传授和使用,日本政府在一八七六年也立法禁止针灸(36),中国的最后行动是一九二九年的全面废止针灸(37).但是在一九三零年代初期,一名小儿科医生承淡安,建议把针灸治疗复活,因为针灸的作用有可能藉由神经学解释.承淡安重新改革之前被用于放血的穴位,把它们从靠近血管的一端移到比较靠近神经的地方;他的改革还包括了把本来的粗针改成我们现在看到的丝状细针(38).改良后的针灸在一九五零及六零年代引起了新中国的革命干部的更多兴趣,除此之外还有一些经过谨慎挑选(按:政治意义上的"谨慎)的传统,民间及实践的疗法被囊括进"科学"医学,目的是要提供一个临时的医疗系统既能够维护危如累卵的大众健康,同时也能提供中国的政治需要并符合马克斯的辩证法.史学家Tim Taylor试图去解构文革中发生的一连串事件,在他一本介绍新中国初期时代中医的书里,解释了为何这个临时的医疗系统藉由符合辩证法和革命精神--有时候几乎是美妙的巧合,而被大力拔高.结果在共产党的领导下,在一九六零年代时针灸从一种边缘疗法晋升到医疗体系里一种重要且高规格的医疗.Tim Taylor认为在这段时间里,中医被系统化和标准化而为我们今天在中国和国外看到的针灸奠定下了基础(39).这段对中医的改造也是"赤脚医生"训练的一部分.赤脚医生们在经过三至六个月的密集医疗及超医疗训练后,在文革时代全国医疗资源缺乏的时候,被分派到乡下地方行医(40).他们提供基本医疗服务,疫苗,生育控制,医疗教育和组织性的消毒行动.但是,毛主席同时也相信传统疗法背后的自然哲学是当时社会及历史状况之下必然产生的一种幼稚的辩证世界观并应该被现代科学取代(41).在记录里毛主席看病时也不做针灸,不用中药(42). 真相是这套在毛主席时代被改造和"消毒"过的针灸和临时凑出来的理论基础在西方世界被当作"传统医疗","中医","东方医疗"和最近的"亚洲医疗"而盛行.今天,在每一个美国及欧洲的大都会区,我们可以找到针灸店,里面的针灸人员不正确的告诉我们用细丝状的钢针轻轻的刺入皮肤以减轻疼痛或是治疗疾病是一向在古中国流传了两千多年的学术性医疗传统.同时,无论针灸支持者的见证,这种用细针轻轻插入人体皮肤上定点的疗法不断的在严谨控制的实验下失败并无法提出有力的证据在病人能够接受治疗的情况下针灸的疗效(43,44).而且不论医疗针灸或是任何一种针刺疗法,没有任何有说服力的证据证明经络作为一个独立于血管的系统存在(45). 参考文献: Veith I (Translator). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. University of California Press, 1st edition. 2002.

Ernst E. Acupuncture – a critical analysis. J Intern Med. 2006; 259(2):125-137.

Ramey D, Buell PD. A true history of acupuncture. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2004;9:269-273.

Dorfer L, Moser M, Spindler K, Bahr F, Egarter-Vigl E, Dohr G. 5200-year-old acupuncture in central Europe? Science. 1998;282(5387):242-243.

Dorfer L, Moser M, Bahr F, et al. A medical report from the Stone Age? Lancet. 1999;354:1023-1025.

Smith, GS, Zimmerman R. Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. American Antiquity 40(4): 433-437. 1975.

Garcia, Hernan and Antonio, Sierra. Wind in the Blood – Mayan Healing & Chinese Medicine. Redwing Books, 1999.

Villoldo A. Shaman, Healer, Sage. Hamony Books, 2000.

Lao Tzu (Author), Mair VH (Translator). Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way. New York. Bantam Books. 1990.

Whorton JC. Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Wu AS. Chinese Astrology. The Career Press, Inc. 2005.

Lo V. The territory between life and death. Essay review. Med Hist. 2003 Apr;47(2):250-8.

Walters D. Chinese Astrology. Aquarian Press. 1987.

Pregadio F. Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Stanford University Press, 1st edition. 2006.

Burkert W. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 1972.

Reid D. Chinese Herbal Medicine. Shambhala. 1987.

Pas JF. Historical Dictionary of Taoism. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1998.

Religion of Tao. Center of Traditional Taoist Studies. www.tao.org. Accessed September 2008.

Fischer-Schreiber I. The Shambhala Dictionary of Taoism. Shambhala. 1st edition. 1996.

Ware J. Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320. The Nei P’ien of Ko Hung (Pao-p’u tzu). Cambridge (Mass.): M.I.T. Press, 1966. Reprint. New York: Dover Publications, 1981.

Holmyard EJ (editor) The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan. New York, E. P. Dutton. 1928.

Kingsley P. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford University Press. 1997.

Copenhaver, BP (Editor). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge. 1992.

Reisch G. Margarita Philosophica, Hoc Est Habituum Sev Disciplinarum Omnium. Basile? 1583.

Jackson WA. A Short Guide to Humoral Medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Sep;22(9):487-9.

Starr D. Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce. Knopf. 1st edition. 1998.

Manilius M (author), Goold GP (Translator). Manilius: Astronomica. Harvard University Press. 1977.

Epler DC Jr. Bloodletting in early Chinese medicine and its relation to the origin of acupuncture. Bull Hist Med. 1980 Fall;54(3):337-67.

Alpher JV (Editor) Oriental Medicine: An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. Serindia. United Kingdom, 1st Edition 1995.

Hall H. Puncturing the Acupuncture Myth. Science-Based Medicine. Posted on October 21, 2008. Accessed November 2008. http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/?p=252.

Unschuld PU. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. University of California Press. 1988.

Barnes LL. Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848. Harvard University Press. 2005.

Kim HB. Handbook of Oriental Medicine. Harmony & Balance Press; 3rd Edition. 2007.

Andrews BJ. History of Pain: Acupuncture and the Reinvention of Chinese Medicine. APS Bulletin. May/June 1999;9(3). 5.

Unschuld PU: The past 1000 years of Chinese medicine. Lancet Suppl SIV9:354, 1999.

Skrbanek P: Acupuncture: Past, present and future, in Stalker D, Glymour C (editors): Examining Holistic Medicine. Buffalo, NY, Prometheus Books. 1985.

Ma KW. The roots and development of Chinese acupuncture: from prehistory to early 20th century. Acupunct Med 1992;10(Suppl):92-9.

Andrews B. Tailoring Tradition: The Impact of Modern Medicine on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1887-1937. In Alleton V and Volkov A (editors). Notions et Percpetions du Changement et Chine. Paris: Collège de France, Institut des Hautes études Chinoises. 1994

Taylor K. Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945-63; A Medicine of Revolution, RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

Scheid V. Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China: Plurality and Synthesis. Duke University Press, 2002.

Schram SR. The Political Thought of Mao Tse-Tung. New York: Praeger Publishers. 1969.

Basser S. Acupuncture: a history. Sci Rev Altern Med 1999;3:34-41.

Ernst E, White A, eds. Acupuncture: A Scientific Appraisal. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1999.

Ernst E. The recent history of acupuncture. Am J Med. 2008 Dec;121(12):1027-8.

Ernst E. Complementary medicine: the facts. Phys Ther Rev 1997;2:49-57.

Acupuncture is astrology with needlesA guest post that demonstrates that acupuncture and astrology have a lot of things in common. Ben Kavoussion August 3, 2009

EDITOR’S NOTE: Because, for the first time in a year and a half, both professional and personal responsibilities precluded my producing a post for Science-Based Medicine, today is the perfect time to present a guest post by Ben Kavoussi. Ben is a medical informatician with an interest in the scientific evaluation of CAM, as well as a Captain in the Army Medical Service Corps. He also studied to become an acupuncturist himself, and his article is a fascinating look at some little known history behind acupuncture that strongly suggests that it is more akin to astrology than you may be aware of. Certainly I had been unaware of it, and I bet most of our readers are unaware of it, too. Enjoy! I’ll be back with a post here next week at the latest. Acupuncture is astrology with needlesby Ben Kavoussi, MS, MSOM, LAc The following is an excerpt of an upcoming article called “The Untold Story of Acupuncture.” It is scheduled to be published in December 2009 in Focus in Alternative and Complementary Therapies(FACT), a review journal that presents the evidence on alternative medicine in an analytic and impartial manner. It argues that if the effects of “real” and “sham” acupuncture do not significantly differ in well-conducted trials, it is because traditional theories for selecting points and means of stimulation are not based on an empirical rationale, but on ancient cosmology, astrology and mythology. These theories significantly resemble those that underlined European and Islamic astrological medicine and bloodletting in the Middle-Ages. In addition, the alleged predominance of acupuncture amongst the scholarly medical traditions of China is not supported by evidence, given that for most of China’s long medical history, needling, bloodletting and cautery were largely practiced by itinerant and illiterate folk-healers, and frowned upon by the learned physicians who favored the use of pharmacopoeia. Heaven is covered with constellations, Earth with waterways, and man with channels.

Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine (黄帝内经, huang di nei jing)1

Acupuncture is presumed to have its origins in blood ritual, magic tattooing and body piercing associated with Neolithic healing practices.2,3 The Neolithic origin hypothesis is supported by the presence of nonfigurative tattoos on the Tyrolean Ice Man–an inhabitant of the Oetztal Alps in Europe–whose naturally preserved 5,200-year-old body displays a set of small cross-shaped tattoos that are located significantly proximal to classical acupuncture points. Medical imaging shows that the middle-aged man suffered from lumbar arthrosis and the cross-shaped tattoos are located at points traditionally indicated for this condition.4,5 Similar nonfigurative tattoos and evidence of therapeutic tattooing, lancing and blood ritual have been found throughout the Ancient world, including the Americas.6,7,8 Health-related tattoos are still prevalent in Tibet, where specific points on the body are needled with a blend of medicinal herbs in the dyes. These practices appear to be largely intended to maintain balance with the natural and spiritual worlds, and also to protect against demonic infestation and malevolence. Seemingly, this Neolithic and Bronze Age lancing heritage, which was intertwined with magic and animism, has evolved in various cultures into codified systems of lancing and venesection for assuring good health and longevity. In addition to treating the impurity or superabundance of blood, in various cultures lancing was also believed to affect the flow of a numinous life-force that is, for instance, called qi (or chi, 氣, pronounced “chee”) in Chinese, prāna(प्राण) in Sanskrit, pneuma (πνεύμα) in Greek, etc.9 In many instances, elements of metaphysics, mythology, mysticism, magic, shamanism, exorcism, astrology and empirical medicine intimately intertwined, making it difficult for modern scholars to interpret them as mutually exclusive categories.

In China, for instance, the numinous force was believed to mirror the Sun’s annual journey through the Ecliptic–meaning its apparent path on the celestial sphere–and to circulate in a network of 12 primary jing luo (經络) known in English as the chinglo channels or simply channels or meridians (a term coined in 1939 by George Soulié de Morant, a French diplomat). These imaginary pathways run from head to toes and interconnect around 360 primary points on the skin.10 There is a strong possibility that the web of these channels was a rudimentary model of the vascular system that was conceptualized according to an episteme-–meaning a set of fundamental beliefs–that was based on astrological principles and mythology. This episteme- also indicated that a person’s health and destiny are determined by the position of the Sun, the Moon, the 5 Planets and the apparition of comets, along with the person’s time of birth.11 In this worldview, each body segment corresponds to one of the 12 Houses of the Chinese zodiac system di zhi (地支) known in English as the Earthly Branches, and which consists of 12 two-hour (30°) divisions of the Ecliptic. The channels are therefore named according to their degree of yin (阴) and yang (阳), from tai yang (太阳) to jue yin(厥阴), which are terms that describe the phases and the positions of the Sun and the Moon.12 Each has five special points designated by the characters 水 (Water), 木 (Wood), 火 (Fire), 土 (Earth) and 金 (Metal) which are also the Chinese terms for Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, Saturn and Venus,13 and seem to correspond to the transit positions of these Planets in the matching House. Each point is also associated with a color, which comes from the visual appearance of the matching Planet in the night sky. Venus is white, Jupiter blue-green, Saturn golden-yellow, Mars red, and Mercury “black,” for it appears to be the dimmest of the five. Each of these points has also an occult connection with a direction, a segment of time, a season, a number set, a taste, a musical note, an internal organ, a body region, etc, in an ancient Chinese metaphysical cosmology often referred to as “correlative cosmology”14 and reminiscent of the esoteric and mystical beliefs held by Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580-c. 490 BC) and his followers, the Pythagoreans.15 In his occult and magico-mystical worldview, the nature of the life-force qi is often described in such terms:16 The major premise of Chinese medical theory is that all the forms of life in the universe are animated by an essential life-force or vital energy called qi. Qi also means “breath” and air and is similar to the Hindu concept of prāna. Invisible, tasteless, odorless, and formless, qi nevertheless permeates the entire cosmos. Qiis transferable and transmutable; digestion extracts qi from food and drink and transfers it to the body, breathing extracts qi from air and transfers it to the lungs. When these two forms of qi meet in the blood-stream, they transmute to form human-qi, which then circulates throughout the body as vital energy. It is the quality and balance of your qi that determines your state of health and span of life.

Other texts refer to qi as a “cosmic spirit that pervades and enlivens all things”17 and “from which the world was created.”18 For instance, the alchemist Ko Hung (葛洪, 2nd – 3rd Century AD) writes that “Man is in qi and qi is in each human being. Heaven and Earth and the ten thousand things all require qi to stay alive. A person that knows how to allow qi to circulate will preserve himself and banish illness that might cause him harm.”19,20 The belief in a “cosmological correlation” between its pathways in the body and the Houses of the Chinese zodiac seems to be based on health and safety beliefs in geocentric cosmology and the related doctrine of “as above, so below” which stipulated that everything in the Heavens has its counterpart on Earth and also in man. The episteme of “as above, so below” and correlative cosmology were prevalent throughout the ancient world, from the Eastern Mediterranean cultures to Northern Europe. It is notably found in the relics of a collection of occult writings called the Corpus Hermetica which are believed to be compiled in Hellenistic Egypt during the 1st or 3rd century AD and are attributed to Hermes Trismegistus (“Thrice-great Hermes”), the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth. The original text was presumably lost or destroyed during the systematic annihilation of non-Christian literature between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. Nonetheless, a section of it known as the Emerald Tablet survived and was translated into Arabic by the Muslim conquerors and later into Latin by John of Seville c. 1140 AD and by Philip of Tripoli c. 1243 AD. An Arabic version of the Tablet by the Muslim polymath and alchemist Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān (أبو موسى جابر بن حيان, c. 721-c. 815 AD) states “That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above, working the miracles of One.”21 Given the prevalence of this set of fundamental beliefs throughout the ancient world, it seems that the natural philosophy that has given rise to the underlying theories of acupuncture in China stems from the same set of beliefs in that were also prevalent along the Silk Road in Persia, Mesopotamia, Egypt and in Greece and that have influenced the health and safety beliefs of pre-Christian Europe, such as the Eastern Mediterranean mystery cults,22 such as Mithraic Mysteries.23 This hypothesis is supported by a statement by Gregor (Gregorius) Reisch (c. 1467-1525) in Margarita Philosophica (Pearl of Wisdom), first published in 1503:24 The pagans believed that the zodiac formed the body of the Grand Man of the Universe. This body, which they called the Macrocosm (the Great World), was divided into twelve major parts, one of which was under the control of the celestial powers reposing in each of the zodiacal constellations. Believing that the entire universal system was epitomized in man’s body, which they called the Microcosm (the Little World), they evolved that now familiar figure of “the cut-up man in the almanac” by allotting a sign of the zodiac to each of twelve major parts of the human body.

Figure 1: European medieval Zodiac Man form John de Foxton’s Liber Cosmographiae, published in 1408. It indicated the repartition of astrological influences on the body which physicians used to determine the auspicious time to let blood. Images courtesy of The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, UK. Given this fundamental belief, European physicians until the 17th century based the practice of medicine on celestial computations, also known as Iatromathematics, astrological medicine orastromedicine. They therefore utilized planetary transition tables called ephemerides or Alfonsine tables to cast a prognostication–meaning a disease outcome prediction based on astrological conjunctions, alignments and the angle between Planets (Aspects)–prior to perform venesection, cupping, cautery, surgery or to prescribe medicines with specific astral powers.25 Disease was then believed to result from interruptions to the flow of the numinous life-force pneuma and an imbalance in the four humors–blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm–which were each associated to an element, a planet, a color, etc, according to European correlative cosmology. Therapy consisted of purging the offending humor and its noxious pressures during favorable Aspects. Most bloodletters would open a vein in the arm, leg or neck with a fine knife called a “lancet.” They would tie off the area with a tourniquet and hold the lancet delicately between thumb and forefinger and strike diagonally or lengthwise into the vein to avoid severing it. They would then collect the blood in a measuring bowl.26 Initially, according to the classical Greek procedure, blood was let from a site near the location of the illness but later physicians drew a smaller amount of blood from a distant site. This procedure not only required the knowledge of the distal cutting points and the precise amount of blood to draw, but also the knowledge of ephemerides to establish the suitable Aspects and timing. Medieval medical manuscripts therefore contained ephemeris charts (volvelles) and the schematic of a body covered with astrological signs, generally known as “Zodiac Man,” which illustrated the specific influences of astrological signs on body parts and organs (Figure 1) and the location of the associated bloodletting points (Figure 2).

Figure 2: European Bloodletting Man from Hans von Gersdorff’s Feldtbüch der Wundartzney, published in 1528. Bloodletting was done by venesection or the application of leeches. Most of these points correspond to key acupuncture points, such as LV3, UB40, SI3, LI4, LI11, SJ3, LU5, etc. Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, US. The allotment of the zodiacs to each of the major parts of the body started at the head with Ares and ran down to the feet, which belonged to Pisces. Cancer was believed to be responsible for diseases of the lungs and the eyes and Scorpio the genital afflictions, for instance.27 The practice of lancing, bloodletting and cupping (الحجامة, hijama) to affect specific organs or to mitigate specific diseases based on a postulated relationship between the internal organs and points on the surface of the skin is still prevalent amongst the Muslims worldwide and nowadays video instructions for it are available, even on YouTube. It is plausible that the same principle is at the origin of acupuncture channels in China28 because the distribution of the regions of astrological influences and the related venesection points portrayed in medieval Islamic and European manuscripts significantly resembles the allocation of master, command, influential, and other key points (Table 1). It is important to note that Greco-Arabic bloodletting was known in China and fragments of Avicenna’s (c. 980 – 1037) The Canon of Medicine (الطب في القانون) were translated during the time of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and published along with other Persian and Arabic texts in the Hui Hui Yao Fang (回回藥方)–meaning the Prescriptions of the Hui Nation–with much of the text in Arabic.29 The correlation between Chinese acupuncture and bloodletting is further supported by the fact that the Chinese character zhēn (針) etymologically refers to lancing with coarse needles or any sharp object used for scarification, bloodletting and minor surgery.30 In addition, As Paul Unschuld points out, the opening of superficial or deep-lying vessels for bloodletting seems to predate the manipulation of qi with needles.31 However, Linda Barnes, in her fascinating book on how China, the Chinese, and their healing practices were imagined in the West from the late Middle Ages through to the mid-19th Century, also argues that there were “sufficient apparent similarities that an early observer might have been excused for imagining that the Chinese and European practices grew from the same conceptual framework.”32 Although she seems to agree with Paul Unschuld’s assessment that acupuncture emerged as an offshoot of bloodletting, she also notes that the early European observers seem to have misunderstood the ways in which the body itself was conceptualized by the Chinese, and assumed that they were simply using a version inferior of the Greek humoral system, and routinely failed to recognize or value an alternate conceptual universe which, in the long run, made it easier for them to dismiss Chinese understandings of the human body. | | |

| Chinese Zodiacs | | | Aries | 0°-30° | Head |

| Tiger | 3AM-5AM | Lung | Taurus | 30°-60° | Neck , throat |

| Rabbit | 5AM-7AM | Large Intestine | Gemini | 60°-90° | Lungs, arms, shoulders |

| Dragon | 7AM-9 AM | Stomach | Cancer | 90°-120° | Chest, breasts, stomach |

| Snake | 9AM-11AM | Spleen | Leo | 120°-150° | Heart, upper back |

| Horse | 11AM-1PM | Heart | Virgo | 150°-180° | Abdomen, digestive system |

| Sheep | 1PM-3PM | Small Intestine | Libra | 180°-210° | Kidneys, lumbar region |

| Monkey | 3PM-5PM | Bladder | Scorpio | 210°-240° | Genitals |

| Rooster | 5PM-7PM | Kidney | Sagittarius | 240°-270° | Hips, thighs |

| Dog | 7PM-9PM | Pericardium | Capricorn | 270°-300° | Knees, bones |

| Pig | 9PM-11PM | San Jiao | Aquarius | 300°-330° | Calves, shins, ankles |

| Rat | 11PM-1AM | Gallbladder | Pisces | 330°-360° | Feet |

| Ox | 1AM-3AM | Liver |

Table 1: Similarities between Muslim and medieval astromedicine and traditional acupuncture theory. For instance, LU7, a point on the Lung meridian is the command point of the head and the neck; LI4, an important point on the Large Intestine meridian controls the face and the throat; SP4 on the Spleen meridian is used for the diseases of the chest, breast and the stomach. The Kidney meridian controls the genitals; an important point related to San Jiao (UB39) is found on the knee; one related to Gallbladder (GB40) on the ankle; and the most important points of the Liver meridian, LV2-3 are on the feet, etc.33 Note that a two-hour segment is the same time measure as 30°, for the celestial sphere moves by 15° every hour. Paradoxically, for most of China’s long medical history, lancing, bloodletting, acupuncture and surgery were practiced by itinerant folk-healers and considered a lower class of therapy compared to the use of pharmacopoeia. As the historian Bridie Andrews Minehan describes:34 The lowly acupuncturists engaged in a great deal of minor surgery, and the two specialties of acupuncture (zhenjiu) and external medicine or surgery (waike) overlapped considerably. Illustrations of the nine needles of acupuncture, featured in many handbooks from the late imperial period, depicted scalpel-like knives, cautery irons, and three-edged bodkins for bloodletting and lancing boils, as well as the fine needles we currently associate with acupuncture.

Andrews Minehan also notes that although needling is often cited in the Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, throughout the history of China relatively little has been written on it elsewhere. Reportedly, by the middle of the second millennium its practice was mostly abandoned, and eventually the Chinese and other Eastern societies took steps to eliminate it altogether.34,35 In 1822 an edict banned its teaching and practice from the Imperial Medical Academy, the institution that provided physicians to the Court. The Japanese government equally prohibited the practice in 1876.36 The final step in China took place in 1929 when it was literally outlawed.37 However, in the early 1930s a Chinese pediatrician by the name of Cheng Dan’an (承淡安, 1899-1957) proposed that needling therapy should be resurrected because its actions could potentially be explained by neurology. He therefore repositioned the points towards nerve pathways and away from blood vessels-where they were previously used for bloodletting. His reform also included replacing coarse needles with the filiform ones in use today.38 Reformed acupuncture gained further interest through the revolutionary committees in the People’s Republic of China in the 1950s and 1960s along with a careful selection of other traditional, folkloric and empirical modalities that were added to scientific medicine to create a makeshift medical system that could meet the dire public health and political needs of Maoist China while fitting the principles of Marxist dialectics. In deconstructing the events of that period, Kim Taylor in her remarkable book on Chinese medicine in early communist China, explains that this makeshift system has achieved the scale of promotion it did because it fitted in, sometimes in an almost accidental fashion, with the ideals of the Communist Revolution. As a result, by the 1960s acupuncture had passed from a marginal practice to an essential and high-profile part of the national health-care system under the Chinese Communist Party, who, as Kim Taylor argues, had laid the foundation for the institutionalized and standardized format of modern Chinese medicine and acupuncture found in China and abroad today.39 This modern construct was also a part of the training of the “barefoot doctors,” meaning peasants with an intensive three- to six-month medical and paramedical training, who worked in rural areas during the nationwide healthcare disarray of the Cultural Revolution era.40 They provided basic health care, immunizations, birth control and health education, and organized sanitation campaigns. Chairman Mao believed, however, that ancient natural philosophies that underlined these therapies represented a spontaneous and naive dialectical worldview based on social and historical conditions of their time and should be replaced by modern science.41 It is also reported that he did not use acupuncture and Chinese medicine for his own ailments.42 It is the reformed and “sanitized” acupuncture and the makeshift theoretical framework of Maoist China that have flourished in the West as “Traditional,” “Chinese,” “Oriental,” and most recently as “Asian” medicine. Nowadays, in every major metropolitan area in the US and in Europe, one can find acupuncture boutiques where practitioners inaccurately claim that gently puncturing the skin with silicon-coated stainless-steel filiform needles is a scholarly medical tradition of ancient China that has been used for over 2,000 years to relieve pain and to treat a variety of diseases. Meanwhile and despite what is reported by the advocates, this gentle insertion of fine needles at specific points on the skin has consistently failed in well-conducted trials to show compelling evidence of efficacy for conditions that are amenable to specific treatments.43,44 And whatever the clinical efficacy of any type of needling therapy, there is still no convincing evidence that meridians exist as discrete entities distinct from blood vessels.45 ADDENDUM: My sincerest apologies to Linda Barnes for citing her work as simply arguing that there are sufficient similarities between needling in China and bloodletting in Europe to warrant the belief that both practices grew from the same conceptual framework. Indeed, the full citation is substantially more nuanced and complex, and corrections were made to reflect her full argument. I appreciate her bringing this to my attention. REFERENCES: - Veith I (Translator). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. University of California Press, 1st edition. 2002.

- Ernst E. Acupuncture – a critical analysis. J Intern Med. 2006; 259(2):125-137.

- Ramey D, Buell PD. A true history of acupuncture. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2004;9:269-273.

- Dorfer L, Moser M, Spindler K, Bahr F, Egarter-Vigl E, Dohr G. 5200-year-old acupuncture in central Europe? Science. 1998;282(5387):242-243.

- Dorfer L, Moser M, Bahr F, et al. A medical report from the Stone Age? Lancet. 1999;354:1023-1025.

- Smith, GS, Zimmerman R. Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. American Antiquity 40(4): 433-437. 1975.

- Garcia, Hernan and Antonio, Sierra. Wind in the Blood – Mayan Healing & Chinese Medicine. Redwing Books, 1999.

- Villoldo A. Shaman, Healer, Sage. Hamony Books, 2000.

- Lao Tzu (Author), Mair VH (Translator). Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way. New York. Bantam Books. 1990.

- Whorton JC. Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Wu AS. Chinese Astrology. The Career Press, Inc. 2005.

- Lo V. The territory between life and death. Essay review. Med Hist. 2003 Apr;47(2):250-8.

- Walters D. Chinese Astrology. Aquarian Press. 1987.

- Pregadio F. Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Stanford University Press, 1st edition. 2006.

- Burkert W. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 1972.

- Reid D. Chinese Herbal Medicine. Shambhala. 1987.

- Pas JF. Historical Dictionary of Taoism. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1998.

- Religion of Tao. Center of Traditional Taoist Studies. www.tao.org. Accessed September 2008.

- Fischer-Schreiber I. The Shambhala Dictionary of Taoism. Shambhala. 1st edition. 1996.

- Ware J. Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320. The Nei P’ien of Ko Hung (Pao-p’u tzu). Cambridge (Mass.): M.I.T. Press, 1966. Reprint. New York: Dover Publications, 1981.

- Holmyard EJ (editor) The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan. New York, E. P. Dutton. 1928.

- Kingsley P. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford University Press. 1997.

- Copenhaver, BP (Editor). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge. 1992.

- Reisch G. Margarita Philosophica, Hoc Est Habituum Sev Disciplinarum Omnium. Basileæ 1583.

- Jackson WA. A Short Guide to Humoral Medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Sep;22(9):487-9.

- Starr D. Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce. Knopf. 1st edition. 1998.

- Manilius M (author), Goold GP (Translator). Manilius: Astronomica. Harvard University Press. 1977.

- Epler DC Jr. Bloodletting in early Chinese medicine and its relation to the origin of acupuncture. Bull Hist Med. 1980 Fall;54(3):337-67.

- Alpher JV (Editor) Oriental Medicine: An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. Serindia. United Kingdom, 1st Edition 1995.

- Hall H. Puncturing the Acupuncture Myth. Science-Based Medicine. Posted on October 21, 2008. Accessed November 2008. https://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/?p=252.

- Unschuld PU. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. University of California Press. 1988.

- Barnes LL. Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848. Harvard University Press. 2005.

- Kim HB. Handbook of Oriental Medicine. Harmony & Balance Press; 3rd Edition. 2007.

- Andrews BJ. History of Pain: Acupuncture and the Reinvention of Chinese Medicine. APS Bulletin. May/June 1999;9(3). 5.

- Unschuld PU: The past 1000 years of Chinese medicine. Lancet Suppl SIV9:354, 1999.

- Skrbanek P: Acupuncture: Past, present and future, in Stalker D, Glymour C (editors): Examining Holistic Medicine. Buffalo, NY, Prometheus Books. 1985.

- Ma KW. The roots and development of Chinese acupuncture: from prehistory to early 20th century. Acupunct Med 1992;10(Suppl):92-9.

- Andrews B. Tailoring Tradition: The Impact of Modern Medicine on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1887-1937. In Alleton V and Volkov A (editors). Notions et Percpetions du Changement et Chine. Paris: Collège de France, Institut des Hautes études Chinoises. 1994

- Taylor K. Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945-63; A Medicine of Revolution, RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

- Scheid V. Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China: Plurality and Synthesis. Duke University Press, 2002.

- Schram SR. The Political Thought of Mao Tse-Tung. New York: Praeger Publishers. 1969.

- Basser S. Acupuncture: a history. Sci Rev Altern Med 1999;3:34-41.

- Ernst E, White A, eds. Acupuncture: A Scientific Appraisal. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1999.

- Ernst E. The recent history of acupuncture. Am J Med. 2008 Dec;121(12):1027-8.

- Ernst E. Complementary medicine: the facts. Phys Ther Rev 1997;2:49-57.

|

|

|Archiver|手机版|导航中医药

( 官方QQ群:110873141 )

|Archiver|手机版|导航中医药

( 官方QQ群:110873141 )